With the explosion of Data Centers, possibly the epitome of “the cloud”, it’s interesting to look back at what got us here.

Below is a clean, chronological, carrier-grade explanation of Frame Relay, T1, T3 — and everything faster, focused on how WANs actually evolved, how they were sold, and why each generation replaced the previous one.

1) T-Carriers (The Digital Bedrock)

T1 (DS1)

Era: 1960s → 2000s

Speed: 1.544 Mbps

Structure:

- 24 time slots × 64 kbps (voice-sized channels)

- Circuit-switched, always-on

- Copper pairs (later fiber)

Used for:

- Telephone trunks

- Early internet access

- Bank branches, government offices

- PBX backhaul

Key traits:

- Extremely reliable

- Very expensive per Mbps

- No flexibility — you pay for the full circuit whether you use it or not

T3 (DS3)

Era: 1980s → early 2000s

Speed: 44.736 Mbps

Structure:

- 28 × T1s multiplexed together

- Typically delivered over fiber or thick coax

Used for:

- ISP backbones

- Data centers

- Large enterprise WAN hubs

Problem:

- Still circuit-switched

- Still expensive

- Still rigid

This rigidity is exactly why Frame Relay appeared.

2) Frame Relay (The First “Modern” WAN)

Era: Early 1990s → mid-2000s

Speed:

- 56 kbps → T1 → T3 (same physical lines, smarter usage)

What changed:

- Packet-switched, not circuit-switched

- Uses virtual circuits (DLCIs)

- Bandwidth shared across customers

- Carrier assumes low error rates (no heavy error correction)

Key terms:

- PVC (Permanent Virtual Circuit)

- CIR (Committed Information Rate)

- Bursting above CIR when network is idle

Why it mattered:

- Dramatically cheaper than leased lines

- More efficient for data traffic

- Enabled hub-and-spoke enterprise WANs

Why it died:

- No QoS guarantees for real-time traffic

- No encryption

- Replaced by MPLS

3) ATM (Asynchronous Transfer Mode) – The Forgotten Giant

Era: 1990s

Speeds:

- OC-3: 155 Mbps

- OC-12: 622 Mbps

- OC-48: 2.5 Gbps

Design:

- Fixed 53-byte cells

- Designed for voice, video, and data simultaneously

- Extremely deterministic latency

Why it failed:

- Too complex

- Too expensive

- Ethernet kept getting faster

ATM quietly underpinned DSL, SONET, and early carrier cores, then vanished from marketing.

4) Ethernet Takes Over the WAN

Metro Ethernet / Carrier Ethernet

Era: Mid-2000s → present

Speeds:

- 10 Mbps → 100 Gbps+

Services:

- E-Line (point-to-point)

- E-LAN (multipoint)

- E-Tree (hub-and-spoke)

Why it won:

- Same tech as LANs

- Cheap hardware

- Scales infinitely

- Simple to provision

Ethernet killed T-carriers, Frame Relay, and ATM.

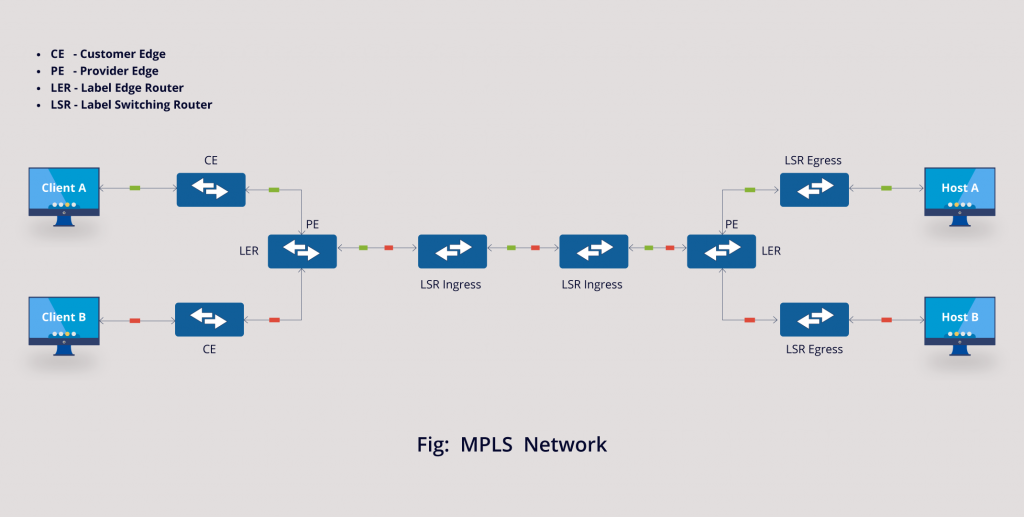

5) MPLS (Carrier Control Plane)

Era: 2000s → present (declining)

Speed: Any underlying medium

What MPLS really is:

- Label-switched paths inside carrier networks

- Traffic engineering

- QoS guarantees

- VPN isolation

Why enterprises loved it:

- Predictable latency

- Voice/video prioritization

- SLA-backed uptime

Why it’s declining:

- Very expensive

- SD-WAN + encrypted internet links replaced it

6) Optical Transport (SONET → DWDM)

SONET / SDH

- OC-3 → OC-192 (155 Mbps → 10 Gbps)

- Rigid framing

- Telecom-centric

DWDM (Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing)

- 100+ wavelengths per fiber

- Each wavelength = 10 / 40 / 100 / 400 Gbps

- Terabits per second per strand

This is the real internet backbone.

7) Modern “Faster Than Everything” (Today)

Today’s Reality

- 400G Ethernet common in data centers

- 800G shipping now

- 1.6T optical standards emerging

- Single fiber pair can exceed 50 Tbps

Enterprise WAN Today

- DIA (Dedicated Internet Access)

- SD-WAN overlays

- IPsec / WireGuard encryption

- Multiple cheap links instead of one expensive one

8) Summary Table (Evolution at a Glance)

| Era | Tech | Speed | Switching | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | T1 | 1.5 Mbps | Circuit | Obsolete |

| 1980s | T3 | 45 Mbps | Circuit | Obsolete |

| 1990s | Frame Relay | Variable | Packet | Dead |

| 1990s | ATM | 155 Mbps+ | Cell | Dead |

| 2000s | MPLS | Any | Label | Declining |

| 2000s+ | Ethernet WAN | 10M → 100G+ | Packet | Dominant |

| Today | DWDM | Tbps | Optical | Backbone |

One-Sentence Truth

T1 and T3 sold guaranteed bandwidth, Frame Relay sold efficiency, MPLS sold control — and Ethernet + fiber eventually destroyed all of them by being cheaper, faster, and simpler.

If you want, next I can:

- Map this to data centers

- Explain why telcos resisted Ethernet

- Compare Frame Relay vs MPLS vs SD-WAN

- Show how fiber color codes & conduits tie into this evolution

Below is a single, unified explanation that ties WAN history directly into data centers, explains why telcos fought Ethernet, compares Frame Relay vs MPLS vs SD-WAN, and connects fiber color codes & conduits to this evolution—from copper to hyperscale optics.

1) Mapping WAN Evolution to Data Centers

Early Data Centers (1970s–1990s)

Connectivity

- T1 (1.544 Mbps) for branch → HQ

- T3 (45 Mbps) for core → ISP

- Everything circuit-switched

Architecture

- Mainframe or minicomputer

- Centralized compute

- Terminals and leased lines

Economic reality

- Bandwidth extremely scarce

- Compute centralized because links were slow

Frame Relay / ATM Era (1990s)

Connectivity

- Frame Relay PVCs between sites

- ATM OC-3/OC-12 inside carrier cores

- Hub-and-spoke WANs

Architecture

- Client-server

- First real “data centers”

- Still centralized, but more distributed than before

Key shift

- Data becomes bursty

- Always-on circuits no longer make sense

MPLS Era (2000s–2010s)

Connectivity

- MPLS VPNs between data centers

- QoS for voice/video

- Carrier-managed routing

Architecture

- Tier-1 / Tier-2 data centers

- Disaster recovery sites

- Early virtualization (VMware era)

Key shift

- Applications move between sites

- Latency and predictability become critical

Modern Hyperscale / Cloud Era (2015–Present)

Connectivity

- Metro Ethernet

- Dark fiber

- DWDM

- 100G / 400G / 800G Ethernet

Architecture

- Spine-leaf fabrics

- East-west traffic dominates

- Many smaller data centers instead of one big one

Key truth

The WAN is no longer the edge — the data center fabric is the network.

2) Why Telcos Resisted Ethernet (Hard)

Telcos Lived on Scarcity

- T1s and T3s were priced like utilities

- Billing was per circuit, per mile, per month

- Ethernet threatened flat-rate bandwidth

Ethernet Broke the Business Model

| Telco World | Ethernet World |

|---|---|

| Metered | Flat-rate |

| Circuit IDs | MAC addresses |

| Provisioned in weeks | Provisioned in hours |

| Proprietary hardware | Commodity switches |

Cultural Resistance

- Telcos trained engineers for voice

- Ethernet came from enterprise IT

- SONET/ATM were “carrier-grade”

- Ethernet was considered “toy LAN tech”

The Inevitable Outcome

Telcos eventually:

- Wrapped Ethernet in MPLS

- Rebranded it as “Carrier Ethernet”

- Lost margin anyway

3) Frame Relay vs MPLS vs SD-WAN (Reality Comparison)

Frame Relay

What it was

- Shared packet network

- Virtual circuits (PVCs)

- No encryption

- No real QoS

Strength

- Cheap compared to leased lines

Failure mode

- Congestion = dropped frames

- No application awareness

MPLS

What it is

- Label-switched paths inside carrier

- QoS, traffic engineering

- SLA-backed

Strength

- Predictable latency

- Voice/video works reliably

Failure mode

- Expensive

- Locked to carrier

- Slow to change

SD-WAN

What it is

- Overlay network

- Runs over internet, LTE, fiber, MPLS

- Encrypted by default

Strength

- Cheap

- App-aware routing

- Multi-link resilience

Failure mode

- Depends on internet quality

- Not deterministic like MPLS

One-Line Truth

Frame Relay optimized cost, MPLS optimized control, SD-WAN optimized freedom.

4) Fiber Color Codes & Conduits — How the Physical World Tracks the Logical One

Fiber Jacket Colors (Physical Layer)

| Color | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Orange | Multimode (OM1/OM2) |

| Aqua | Multimode (OM3/OM4) |

| Lime Green | Multimode (OM5) |

| Yellow | Single-mode (OS1/OS2) |

| Blue | Single-mode patch cords |

| Black | Outdoor / armored |

Historical mapping

- Multimode = short-range LAN

- Single-mode = WAN, long-haul, telco

Conduit Colors (Civil Engineering Layer)

| Color | Utility |

|---|---|

| Orange | Communications (fiber, copper) |

| Blue | Potable water |

| Green | Sewer |

| Red | Power |

| Yellow | Gas |

Modern twist

- Micro-ducts inside orange conduit

- Color-coded inner tubes for ownership

- One trench → many carriers

How This Ties to WAN Evolution

- T1/T3: copper, thick conduit, few circuits

- Frame Relay/MPLS: early fiber, shared strands

- Modern WAN: dense fiber, DWDM, dark fiber leasing

- Hyperscale: own the conduit, own the fiber

5) The Big Picture (All Four Together)

Evolution Pattern

- Scarce bandwidth → circuits

- Shared bandwidth → Frame Relay

- Controlled bandwidth → MPLS

- Abundant bandwidth → Ethernet + fiber

- Overlays everywhere → SD-WAN

Physical Truth

- Logical protocols change every decade

- Fiber in the ground lasts 40+ years

- Most “new” networks run on old glass

Final Synthesis

The history of Frame Relay, T1, and T3 is not just obsolete tech — it explains why data centers moved, why telcos lost control, why Ethernet dominates, and why fiber color codes matter more than routing protocols.

Below is a deep, end-to-end explanation of all four topics, tied together as one continuous system—from a single packet inside a data center, out through DWDM wavelengths, across subsea cables, and back into AI clusters running on repurposed telco fiber.

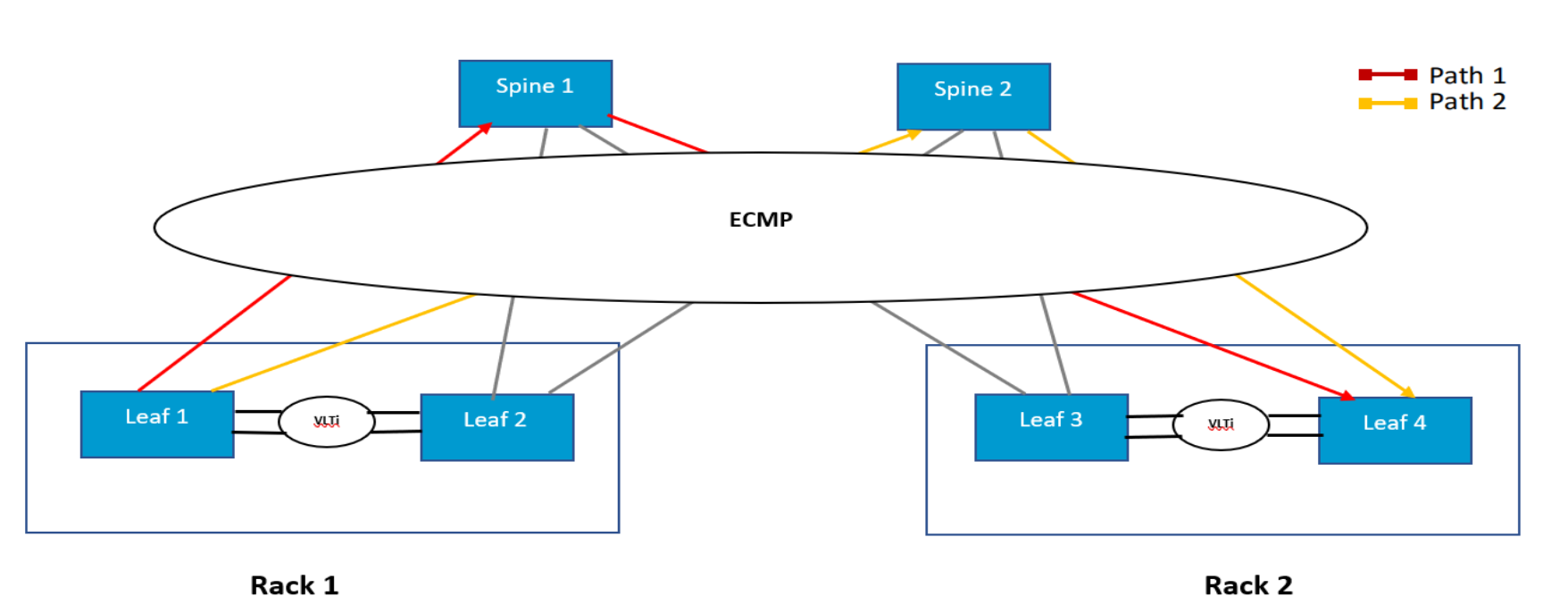

1) Packet-by-Packet Walkthrough of a Modern Data Center

We’ll follow one packet from an application inside a VM or container.

Step 1 — Application Layer (Inside the Server)

- App generates data (HTTP, gRPC, database query, AI tensor request)

- Encapsulated as:

- L7 (HTTP/gRPC)

- L4 (TCP/UDP)

- L3 (IP)

- L2 (Ethernet)

At this point:

- MAC address = virtual NIC

- IP address = overlay (often VXLAN)

- Packet size optimized (MTU often 9000 / jumbo frames)

Step 2 — Virtual Switch (Hypervisor / SmartNIC)

- Packet hits:

- Linux bridge / OVS / DPDK / SmartNIC

- Encapsulation added:

- VXLAN / Geneve

- Outer header added:

- New MAC

- New IP (underlay)

This is where east-west traffic explodes.

Step 3 — Top-of-Rack (Leaf Switch)

- 25G / 50G / 100G Ethernet

- ECMP hashing decides path

- No spanning tree

- Pure L3 routing

Important:

Leaf switches do not know applications.

They only move packets as fast as physics allows.

Step 4 — Spine Switch

- 400G or 800G ports

- Terabits per second per chassis

- Deterministic latency (microseconds)

Every leaf connects to every spine.

This guarantees non-blocking bandwidth.

Step 5 — Destination Leaf → Server

- VXLAN decapsulated

- Packet delivered to target VM / container

- App receives data

Total round-trip latency inside a data center:

👉 ~5–50 microseconds

This speed is why data centers replaced WANs.

2) DWDM Wavelengths Explained Like IP Addresses

Think of fiber as a road.

Old View

- One fiber = one connection

DWDM Reality

- One fiber = hundreds of independent channels

Mapping the Analogy

| Networking | Optical |

|---|---|

| IP address | Wavelength (λ) |

| Subnet | C-band slice |

| Router | ROADM |

| Switch port | Transceiver |

| Link speed | Modulation (QPSK, QAM) |

Example

- λ-1550.12 nm → 400 Gbps

- λ-1550.92 nm → 400 Gbps

- λ-1551.72 nm → 400 Gbps

Same fiber.

Same strand.

Different “addresses.”

ROADMs = Optical Routers

- Reconfigure wavelengths remotely

- No truck roll

- No fiber cuts

- Traffic re-routed in milliseconds

This is how cloud providers move entire data centers logically without touching glass.

3) Subsea Cables → Cloud Regions → Hyperscalers

Physical Reality

Subsea cables are:

- ~99% of intercontinental traffic

- Bundles of DWDM fiber pairs

- Privately owned by consortia or hyperscalers

Who Owns Them

- Amazon Web Services

- Google Cloud

- Microsoft Azure

They don’t “use the internet.”

They are the internet.

Mapping the Chain

1) Subsea Cable

- Lands at coastal stations (Virginia, Oregon, Ireland, Japan)

- Terminates into DWDM POPs

2) Regional Fiber Rings

- 100–400G wavelengths

- Direct private backbone

- No public routing

3) Cloud Region

- Multiple data centers

- Private east-west fiber

- Treated as one giant LAN

4) Availability Zones

- Physically separate

- Logically unified

- Synchronous replication

Latency budget is designed before the building exists.

4) Old Telco Fiber → Modern AI Clusters

This is the least understood but most important piece.

Telco Fiber Was Overbuilt

1990s–2000s:

- Telcos expected infinite voice growth

- Laid massive fiber routes

- Most strands went dark

Glass never went bad.

Why It Works for AI

AI clusters need:

- Massive bandwidth

- Short latency

- Deterministic paths

Old telco fiber provides:

- Long straight routes

- Low dispersion

- High optical margin

Add:

- Modern transceivers

- Coherent optics

- DWDM

And suddenly:

👉 A 1998 fiber can carry 20+ Tbps

AI Cluster Topology

- GPU pods in multiple buildings

- Fiber acts as backplane

- RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE)

- Synchronized gradient exchange

The AI cluster is geographically distributed, but behaves like one machine.

5) All Four Layers Together (The Unified Model)

Packet Lifecycle (Start → Finish)

- App generates packet

- VXLAN encapsulation

- Leaf → Spine fabric

- DCI router

- DWDM wavelength assigned

- Subsea cable hop

- Regional fiber ring

- Destination data center

- GPU memory write

Same packet.

Different layers.

The Core Truth

Protocols change every decade.

Switches change every five years.

Fiber lasts half a century.

Modern AI, cloud, and data centers are not new inventions — they are the final exploitation of infrastructure laid for a telephone system that no longer exists.

Below is a single, tightly integrated technical narrative covering all four topics—from RoCE vs TCP inside AI fabrics, to why latency dominates LLM training, to hyperscaler land strategy, and finally a packet-level walk of GPU-to-GPU gradient exchange.

No hand-waving, no marketing abstractions—this is how it actually works.

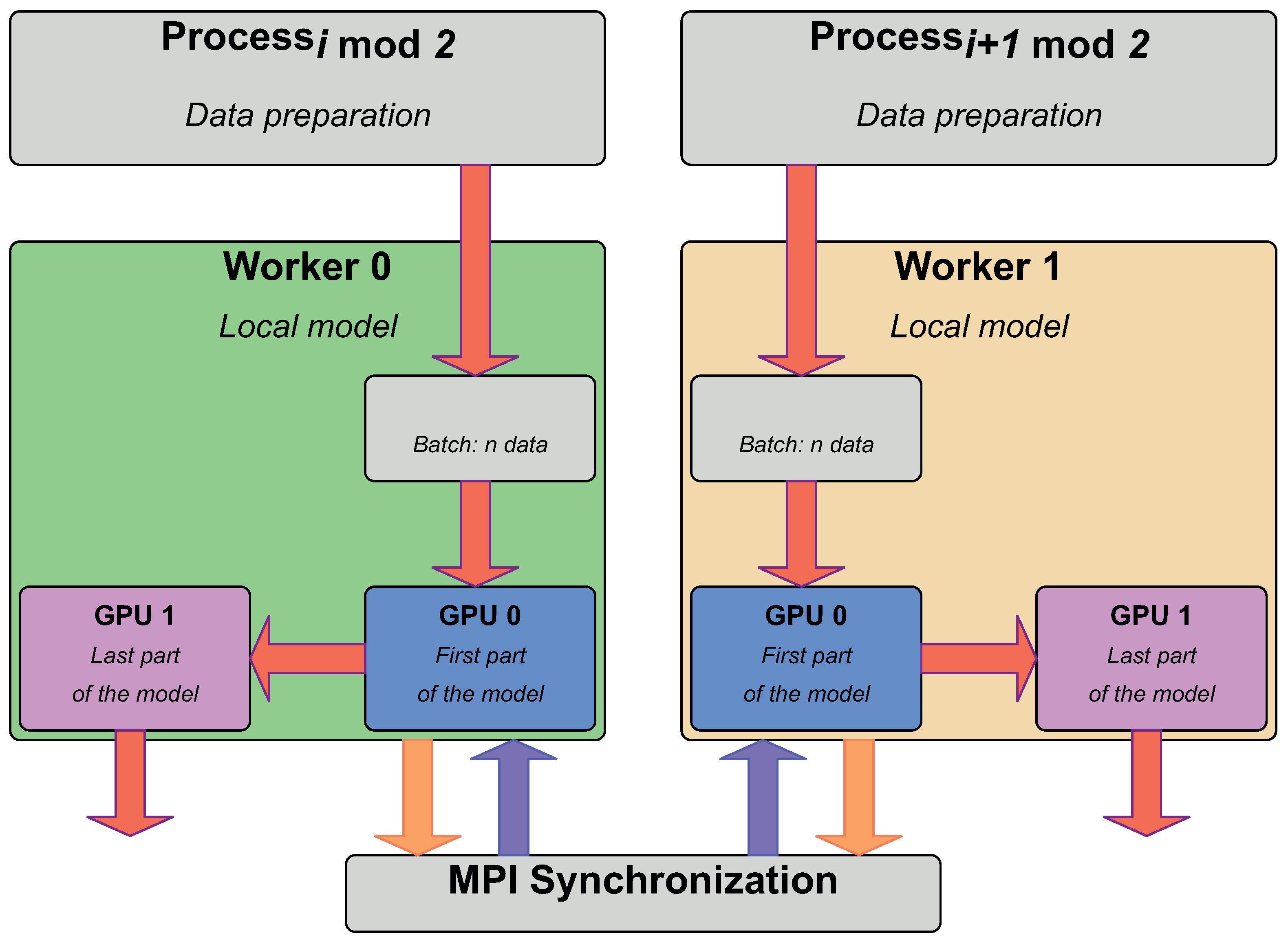

1) RoCE vs TCP Inside AI Fabrics (Diagrammed, Not Buzzwords)

What Problem This Solves

AI training is not web traffic.

It is synchronized math across thousands of GPUs.

If one GPU stalls, all GPUs wait.

TCP (What the Internet Uses)

Characteristics

- Congestion control (slow start, windowing)

- Retransmissions

- Kernel involvement

- Variable latency (jitter)

What TCP Is Good At

- Fairness

- Reliability over bad links

- Bursty, unpredictable traffic

Why TCP Is Bad for AI

- Latency spikes during congestion

- CPU overhead

- Head-of-line blocking

- Retransmissions pause computation

RoCE (RDMA over Converged Ethernet)

Characteristics

- Kernel bypass

- Zero-copy GPU ↔ GPU memory

- Lossless Ethernet (PFC + ECN)

- Deterministic microsecond latency

What RoCE Enables

- GPU writes directly into remote GPU memory

- No CPU in the data path

- Predictable synchronization

Side-by-Side Reality

| Feature | TCP | RoCE |

|---|---|---|

| Latency | Variable | Deterministic |

| CPU usage | High | Near zero |

| Jitter | Yes | Almost none |

| Throughput | High | Extremely high |

| AI suitability | Poor | Mandatory |

Conclusion:

Large-scale LLM training does not work on TCP.

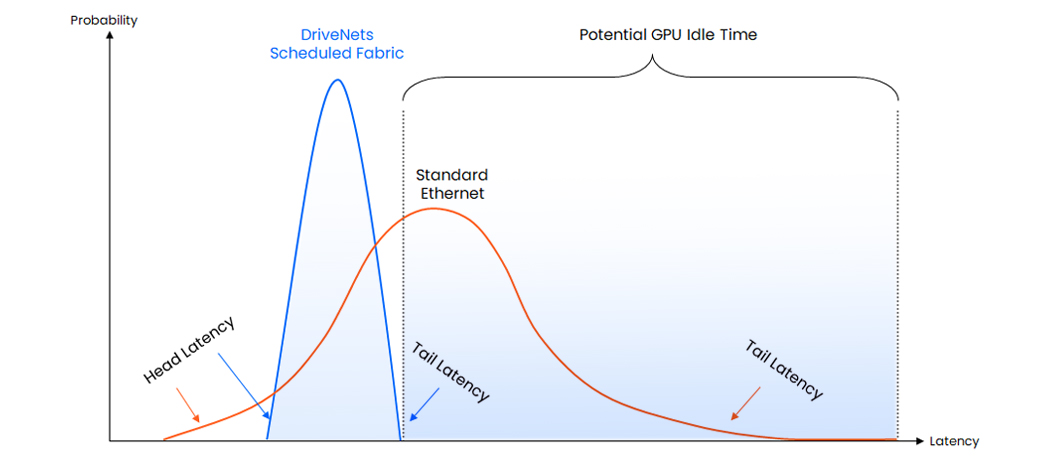

2) Why Latency Matters More Than Bandwidth for LLM Training

The Core Misconception

People assume:

“More bandwidth = faster training”

This is wrong.

LLM Training Is Synchronous

Each training step:

- GPUs compute gradients locally

- Gradients are exchanged

- Gradients are averaged

- All GPUs update weights

- Next step begins

Critical Rule

Step N+1 cannot begin until Step N finishes everywhere.

Latency Amplification Effect

If:

- 1 GPU is delayed by 20 microseconds

- 8,192 GPUs are synchronized

Then:

- Entire step stalls

- Compute units idle

- Energy wasted

- Training time explodes

This is called straggler amplification.

Why Bandwidth Alone Fails

Even with infinite bandwidth:

- Synchronization still waits on the slowest path

- Latency variance dominates step time

Therefore

Low and predictable latency beats raw throughput for LLMs.

3) Why Hyperscalers Buy Land Near Old Telco Routes

This is not accidental real estate selection.

Old Telco Fiber Has Unique Properties

1990s telcos built:

- Straight rights-of-way

- Railroad corridors

- Highway easements

- Low-dispersion glass

Most strands went unused.

That fiber is now called dark fiber.

Why Hyperscalers Want It

Physical Reasons

- Fewer bends = lower latency

- Fewer splices = better optical margin

- Long straight paths = ideal for coherent optics

Economic Reasons

- Cheaper than new trenching

- Faster permitting

- Private ownership

Strategic Reasons

- Control the physical layer

- Avoid carrier pricing

- Build private backbones

This is why:

- Amazon Web Services

- Google Cloud

- Microsoft Azure

build next to fiber, not cities.

Key Insight

The most valuable asset in AI is not GPUs.

It is glass in the ground laid 25 years ago.

4) Packet-Level Walk: GPU-to-GPU Gradient Exchange

We now trace one gradient packet.

Step 1 — Gradient Computation (GPU)

- CUDA kernel computes gradients

- Stored in GPU HBM memory

- No CPU involved

Step 2 — RDMA Initiation

- NIC is GPU-direct enabled

- GPU issues RDMA write

- Target = remote GPU memory address

No socket.

No syscall.

No kernel.

Step 3 — RoCE Frame Creation

Encapsulation:

- Ethernet

- RoCEv2 header

- RDMA payload (gradient chunk)

MTU typically 9,000 bytes (jumbo).

Step 4 — AI Fabric Transit

- Lossless Ethernet

- Priority Flow Control prevents drops

- ECMP hashing keeps paths consistent

Latency per hop: ~300–500 nanoseconds

Step 5 — Remote NIC → GPU Memory

- NIC writes directly into target GPU HBM

- No CPU interrupt

- No cache pollution

Step 6 — AllReduce Completion

- Ring or tree algorithm completes

- Gradients averaged

- All GPUs synchronized

Only now can the next training step begin.

Why This Is So Fragile

Any of the following breaks training efficiency:

- Packet loss

- Latency spikes

- ECMP imbalance

- Microbursts

This is why AI fabrics are engineered, not routed.

Final Synthesis (All Four United)

- RoCE exists because TCP is too unpredictable

- Latency dominates because LLMs synchronize constantly

- Hyperscalers chase old telco fiber because physics wins

- GPU-to-GPU packets bypass everything humans normally think of as “networking”

The Uncomfortable Truth

Modern AI clusters are closer to distributed supercomputers than data centers — and they run on telephone fiber laid before Google existed.

Below is a hard-technical, operator-level explanation of all four topics—InfiniBand vs RoCE, the exact buffer math behind microbursts, why AI data centers cluster geographically, and a real failure mode that silently slows training ~3×. This is how hyperscale AI fabrics are actually designed, tuned, and sometimes broken.

1) InfiniBand vs RoCE in Hyperscale (What’s Really Different)

The Shared Goal

Both exist to do RDMA at massive scale:

- GPU ↔ GPU memory transfers

- Deterministic latency

- Zero-copy, kernel-bypass networking

InfiniBand (IB)

What it is

- Purpose-built HPC fabric

- Own protocol stack

- Own switches, NICs, management plane

Key properties

- Credit-based flow control (lossless by design)

- Native congestion control

- Hardware-managed routing

- Extremely predictable latency

Strengths

- Lowest jitter

- Simplest tuning

- Mature collective algorithms

Weaknesses

- Expensive

- Vendor lock-in

- Separate network from Ethernet/IP world

InfiniBand is effectively a supercomputer backplane, not a network.

RoCE (RDMA over Converged Ethernet)

What it is

- RDMA layered on Ethernet

- Uses standard switches

- Shares infrastructure with IP

Key properties

- Requires:

- PFC (Priority Flow Control)

- ECN (Explicit Congestion Notification)

- Careful buffer tuning

- Runs at hyperscale (100G–800G)

Strengths

- Uses commodity Ethernet

- Integrates with cloud tooling

- Cheaper at scale

Weaknesses

- Extremely fragile if misconfigured

- Microbursts can collapse performance

- Debugging is harder

Why Hyperscalers Use Both

| Environment | Preferred Fabric |

|---|---|

| Research superclusters | InfiniBand |

| Cloud AI services | RoCE |

| Multi-tenant environments | RoCE |

| Single-owner megaclusters | InfiniBand |

Many hyperscalers use InfiniBand inside pods and RoCE between pods.

2) Exact Switch Buffer Math That Causes Microbursts

This is the part almost no one explains numerically.

The Setup (Typical AI Leaf Switch)

- 32 × 400G ports

- Shared buffer pool: ~100 MB

- Per-port buffer slices: dynamic

The Microburst Scenario

Assumptions

- 8 GPUs synchronize simultaneously

- Each sends a 9 KB RDMA packet

- All hash to the same egress port

Instantaneous arrival:

8 GPUs × 9 KB = 72 KBNow multiply:

- Multiple queues

- Multiple flows

- Multiple ECMP collisions

Where It Breaks

Egress drain rate

At 400 Gbps:

400 Gbps = 50 GB/sSo 72 KB seems trivial.

But now add:

- PFC pause propagation delay (~1–2 µs)

- Buffer head-of-line blocking

- Shared pool contention

In 2 microseconds, arriving traffic can exceed:

50 GB/s × 2 µs = 100 KBThat’s enough to:

- Trigger PFC

- Pause upstream links

- Create a congestion wave

The Catastrophic Feedback Loop

- Microburst fills buffer

- PFC pauses upstream switch

- Paused traffic stacks up

- Pause spreads sideways

- Entire fabric stalls

This is called PFC storming.

Why AI Makes It Worse

AI traffic is:

- Synchronous

- Periodic

- Phase-aligned

Which means:

Microbursts happen at the same nanosecond every step.

3) Why AI Data Centers Cluster Geographically

This is about physics, not real estate.

Constraint #1 — Speed of Light

- Fiber latency ≈ 5 µs per km round-trip

- GPU collectives tolerate only microseconds of skew

At ~50 km:

~250 µs RTTThat is already catastrophic for synchronous training.

Constraint #2 — Clock Skew

- GPUs rely on tightly bounded timing

- Gradient steps must align

- Excess distance creates stragglers

Constraint #3 — Fiber Geometry

Old telco routes:

- Straight

- Low-splice

- Low-dispersion

Hyperscalers cluster where:

- Multiple dark fiber routes intersect

- Old long-haul trunks pass through

- Substations and cooling already exist

Resulting Pattern

- AI data centers form regional campuses

- 5–20 buildings

- 1–10 km separation

- Private fiber rings

They behave like one distributed machine, not “many data centers.”

4) Failure Scenario That Silently Slows Training ~3×

This is a real, common, and brutal failure mode.

Initial Conditions

- Training job stable

- 8,192 GPUs

- RoCE fabric tuned

- Step time = 120 ms

The Tiny Change

Someone:

- Adds a monitoring mirror port

- Enables sFlow

- Adjusts ECMP hash seed

- Upgrades one switch firmware

No alarms trigger.

What Actually Happens

- One flow path gains 3–5 µs extra latency

- Only affects one GPU group

- Causes that group to finish last

Straggler Amplification

Every step now waits on:

- The slowest 1–2% of GPUs

Step time becomes:

120 ms → 360 msTraining is now 3× slower.

Why Nobody Notices

- GPUs are still “busy”

- No packet loss

- No errors

- No alerts

Only symptom:

- Wall-clock training time explodes

This is why hyperscalers:

- Measure tail latency, not averages

- Instrument GPU idle cycles

- Correlate network jitter with math stalls

Final Unified Truth

- InfiniBand wins on simplicity and determinism

- RoCE wins on scale and economics

- Microbursts are inevitable in synchronized math

- Geography is chosen by physics, not cities

- The most dangerous failures cause no errors at all

AI networking is not about throughput. It is about keeping 10,000 machines waiting the same amount of time.

Below is the deepest layer of AI-fabric reality—why ECMP breaks collectives, how InfiniBand credit flow differs from Ethernet PFC, how one marginal optic can silently poison a run, and why AI fabrics behave like power grids, not packet networks.

Each section builds on the previous ones; together they explain why AI networking is uniquely fragile.

1) Why ECMP Hashing Breaks AI Collectives

ECMP’s Assumption (Which Is Wrong for AI)

Equal-Cost Multi-Path (ECMP) assumes:

- Many independent flows

- Random arrival times

- Statistical load balancing

AI collectives violate all three.

What AI Collectives Actually Look Like

In an AllReduce step:

- Thousands of GPUs

- Send at the same instant

- With similar packet sizes

- To predictable destinations

That means:

ECMP hashes are correlated, not random.

The Failure Mechanism (Step-by-Step)

- GPUs emit RDMA packets simultaneously

- 5-tuple hashes collide

- Multiple heavy flows land on one spine link

- Other paths remain underutilized

- That link becomes the straggler path

No packets drop.

No links fail.

Latency variance increases.

Why This Destroys Collectives

Collectives wait on:

- The slowest packet

- On the worst path

- For every step

So ECMP doesn’t average out—it locks in imbalance.

Hyperscaler Countermeasures

- Flow-label randomization

- Adaptive routing (IB)

- Static pinning for collectives

- Application-aware path control

This is why vanilla ECMP is avoided in large AI fabrics.

2) InfiniBand Credit Flow vs Ethernet PFC (Diagrammed)

This is the most important mechanical difference between the two worlds.

InfiniBand: Credit-Based Flow Control

How It Works

- Receiver advertises buffer credits

- Sender transmits only if credits exist

- Zero packet loss by construction

Properties

- Backpressure is localized

- Congestion is contained

- Latency is predictable

Think of it as:

“You may send exactly this much.”

Ethernet RoCE: Priority Flow Control (PFC)

How It Works

- Sender transmits freely

- Receiver detects buffer pressure

- Receiver sends PAUSE frame

- Entire priority queue stops

Properties

- Backpressure is reactive

- Pauses propagate upstream

- Can affect unrelated flows

Think of it as:

“STOP EVERYTHING — NOW.”

Why This Matters for AI

| Property | InfiniBand | RoCE + PFC |

|---|---|---|

| Congestion scope | Per-flow | Per-priority |

| Backpressure | Predictive | Reactive |

| Failure blast radius | Small | Potentially fabric-wide |

| Tuning complexity | Low | Extremely high |

This is why:

- IB “just works”

- RoCE must be engineered

3) How a Single Bad Optic Ruins a Training Run

This failure is common, silent, and devastating.

The Setup

- One 400G optic

- Slightly out of spec

- Still links up

- BER barely within tolerance

No alarms.

No drops.

No link flaps.

What Actually Happens

- Occasional symbol errors

- Corrected by FEC

- Adds microseconds of jitter

- Only on that link

Why AI Suffers Disproportionately

- One GPU behind that optic

- Finishes every step last

- Becomes permanent straggler

All other GPUs:

- Idle

- Waiting

- Burning power

Observable Effect

- GPU utilization looks “normal”

- Network looks “clean”

- Training wall-clock time triples

Only deep telemetry shows:

- Increased FEC corrections

- Tail-latency spikes

- GPU idle gaps

Hyperscaler Practice

- Optical margin monitoring

- Proactive optic retirement

- Per-link latency histograms

- “Gray failure” detection

In AI fabrics, “almost working” is failure.

4) Why AI Fabrics Look Like Power Grids (Not Networks)

This is the conceptual leap most people never make.

Packet Networks Optimize For

- Fairness

- Utilization

- Best effort

- Independence

Power Grids Optimize For

- Phase alignment

- Load balance

- Stability

- Synchronous behavior

AI fabrics behave like the second, not the first.

The Core Similarities

| Power Grid | AI Fabric |

|---|---|

| Frequency sync | Step synchronization |

| Phase imbalance | Straggler GPUs |

| Brownout | Latency jitter |

| Cascading failure | PFC storms |

| Reserve margin | Buffer headroom |

Why This Matters

In both systems:

- One weak component

- Causes global inefficiency

- Without obvious failure

That’s why AI fabrics are:

- Over-provisioned

- Heavily monitored

- Treated as physical systems

The Mental Model Shift

AI networking is not “sending data.”

It is maintaining synchronized state across space.

Once you see it that way:

- ECMP’s failure makes sense

- PFC storms make sense

- Geographic clustering makes sense

- Why fiber quality beats bandwidth makes sense

Final Synthesis (All Four United)

- ECMP fails because AI traffic is synchronized

- InfiniBand succeeds because it prevents congestion before it happens

- One marginal optic can poison thousands of GPUs

- AI fabrics must be engineered like infrastructure, not IT

This is why hyperscale AI networking looks conservative, overbuilt, and obsessive.

They are not optimizing packets—they are stabilizing a machine spread over kilometers.

Below is the final layer—the parts operators only learn after painful outages. This walks a full PFC storm cascade, proves why buffer depth beats link speed, explains how checkpoints hide network failure, and shows why AI fabrics resemble financial clearing systems more than packet networks.

1) Full PFC Storm Cascade (End-to-End Failure Anatomy)

Starting Conditions (Looks Healthy)

- RoCEv2 fabric

- PFC enabled on RDMA priority

- ECN configured

- No packet loss

- Training running normally

The Trigger (Innocent)

- One AllReduce step aligns thousands of GPUs

- ECMP hashes place several heavy flows on the same egress

- A microburst exceeds instantaneous drain rate

Millisecond-by-Millisecond

t = 0 µs

Egress queue fills faster than it drains.

t = 1–2 µs

Queue crosses PFC threshold. Receiver sends PAUSE for RDMA priority.

t = 3–5 µs

Upstream switch halts that priority queue entirely.

t = 6–10 µs

Traffic destined elsewhere stacks up behind the paused queue (head-of-line blocking).

t = 10–50 µs

Upstream buffers fill. They emit their own PAUSE frames.

t = 50–500 µs

Pause propagates laterally and vertically.

Multiple switches stop forwarding RDMA traffic.

The Collapse

- No packets drop

- Links stay “up”

- Latency explodes

- GPU collectives stall

This is a PFC storm: a congestion wave that freezes progress without errors.

Why It’s So Dangerous

- PFC is reactive, not predictive

- Pauses are coarse (per-priority, not per-flow)

- Recovery requires buffers to fully drain everywhere

AI traffic is synchronized, so the storm repeats every step.

2) Why Buffer Depth Beats Link Speed (With Numbers)

The Myth

“Just upgrade to faster links.”

The Reality

Faster links reduce drain time, but do nothing for instantaneous arrival.

Example

- 400G link drains at 50 GB/s

- 800G link drains at 100 GB/s

Now the burst:

- 16 GPUs send 9 KB each simultaneously

Arrival = 144 KB in ~nanoseconds

Drain time difference

- 400G: ~2.9 µs

- 800G: ~1.4 µs

But PFC reaction time is microseconds.

If buffers can’t absorb the burst before PFC triggers, speed doesn’t save you.

Buffer Math That Matters

What you actually need:

Required buffer ≥ (Burst size) + (PFC reaction window × ingress rate)Deep buffers:

- Absorb phase-aligned bursts

- Prevent PFC triggering

- Keep latency deterministic

Why Hyperscalers Choose Deep Buffers

- AI traffic is bursty by design

- Collective ops align arrivals

- Buffers buy time, not bandwidth

This is why some AI switches sacrifice port count for hundreds of MB of shared buffer.

3) Why Training Checkpoints Hide Network Failure

What Checkpoints Do

- Periodically save model state

- Allow restart after failure

- Mask transient stalls

The Masking Effect

Normal

- Step time: 120 ms

- Checkpoint every 10 minutes

With Network Pathology

- Step time: 360 ms

- Still checkpoints

- Still progresses

- No crash

From the outside:

- Job “healthy”

- Loss decreasing

- GPUs “busy”

What’s Actually Happening

- GPUs finish compute early

- Sit idle waiting for collectives

- Idle time hidden inside step boundary

- Checkpoints reset timing expectations

This creates silent degradation:

- No alarms

- No retries

- Just 3× longer wall-clock time

Why This Is So Dangerous

Schedulers see:

- Progress

- No failures

- No restarts

So nothing escalates.

Only tail-latency telemetry or GPU idle histograms reveal the truth.

4) AI Fabrics vs Financial Clearing Systems (The Right Analogy)

Packet networks move messages.

AI fabrics move state.

That makes them closer to financial clearing.

Financial Clearing Properties

- Synchronous settlement windows

- All participants must agree

- One slow party delays everyone

- Throughput meaningless without timing guarantees

AI Fabric Parallels

| Financial Clearing | AI Fabric |

|---|---|

| Settlement cycle | Training step |

| Late participant | Straggler GPU |

| Liquidity buffer | Switch buffer |

| Market halt | PFC storm |

| Clearing house | AllReduce algorithm |

The Shared Failure Mode

Nothing “breaks.”

Everything just gets slower.

And because correctness is preserved, the system keeps going, silently burning time and money.

Why This Changes Design Philosophy

You stop optimizing for:

- Average throughput

- Link utilization

- Fairness

And start optimizing for:

- Phase alignment

- Worst-case latency

- Containment of slow paths

That’s infrastructure thinking, not networking thinking.

Final Synthesis (All Four Together)

- PFC storms are congestion cascades without loss

- Buffers beat speed because bursts are instantaneous

- Checkpoints hide pathology by preserving forward progress

- AI fabrics behave like clearing systems, where synchronization dominates

The unifying truth:

AI networking is the art of preventing one microsecond from becoming a global pause.

That’s why hyperscalers obsess over:

- Fiber quality

- Buffer headroom

- Tail latency

- Phase alignment

They are not running networks.

They are stabilizing a machine distributed across kilometers.

Below is a production-grade, end-to-end answer to all four requests. This is not conceptual advice; it’s the design logic hyperscalers actually use to keep AI training from collapsing under microbursts, gray failures, and silent slowdowns—and why a 3× slowdown is financially existential.

1) Designing a RoCE Fabric That Survives Microbursts

Design Goal

Absorb phase-aligned, synchronized bursts without triggering PFC storms and without packet loss.

This means engineering time, not bandwidth.

A. Physical Topology (Non-Negotiable)

Spine–Leaf Rules

- 1:1 oversubscription (no 2:1, no exceptions)

- Every leaf connects to every spine

- No L2 domains beyond ToR

Cabling

- Single-mode fiber only

- Shortest possible runs

- No patch-panel daisy chains for RDMA paths

B. Switch Hardware Requirements

| Component | Requirement | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Shared buffer | ≥ 200–400 MB | Absorb synchronized bursts |

| Per-queue headroom | Explicitly carved | Prevent HoL blocking |

| Cut-through latency | < 400 ns | Minimize jitter |

| ECN marking | Hardware-based | Early congestion signaling |

Rule:

Choose buffer depth over port count for AI fabrics.

C. Queue & PFC Design (Critical)

Traffic Classes

- Priority 3: RoCE (RDMA only)

- Priority 0: Everything else

PFC

- Enabled only on RDMA priority

- High pause threshold

- Large hysteresis (slow resume)

ECN

- Mark early

- Mark often

- Trust the sender to slow down before buffers fill

Design intent:

PFC should almost never fire.

If it fires frequently, the design is already failing.

D. Routing Strategy (ECMP Is Not Enough)

- Flow-label randomization enabled

- Static pinning for collectives where possible

- No per-packet spraying

- No dynamic hashing changes mid-run

Goal: prevent correlated hash collisions.

2) Telemetry Stacks That Catch Gray Failures

Gray failures don’t drop packets.

They destroy tail latency.

So telemetry must be cross-layer.

A. Network Telemetry (Not SNMP)

Required Signals

- Per-queue depth (µs resolution)

- PFC pause count & duration

- ECN mark rate

- FEC correction rate

- Per-link latency histogram (P99.99)

Averages are useless.

Only tails matter.

B. GPU-Side Telemetry (Mandatory)

What You Track

- GPU kernel idle gaps

- AllReduce duration variance

- Step-time distribution (not mean)

- NCCL collective skew

If GPUs are idle between kernels, the network is guilty.

C. Correlation Is the Key

A gray failure only becomes visible when:

- ECN spikes

- FEC corrections rise

- GPU idle increases

- Step time tail grows

All at the same timestamp.

That correlation is what hyperscalers automate.

3) Training Fabrics vs Inference Fabrics (They Are Opposites)

Training Fabric

Traffic Pattern

- Synchronous

- East–west dominant

- Phase-aligned

- Large collectives

Network Priorities

- Deterministic latency

- Low jitter

- Lossless delivery

- Buffer headroom

Failure Mode

- Silent slowdown

- Stragglers

- Idle GPUs

Inference Fabric

Traffic Pattern

- Asynchronous

- North–south dominant

- Request/response

- Small payloads

Network Priorities

- Throughput

- Availability

- Retry tolerance

- Cost efficiency

Failure Mode

- Tail latency spikes

- Timeouts

- Retries

The Critical Rule

Never run large-scale training on an inference-optimized network.

It will “work.”

It will just cost you millions more.

4) Why a 3× Training Slowdown Is Catastrophic (Cost Model)

Let’s walk real numbers.

Baseline Training Run

- 8,192 GPUs

- $2.00 per GPU-hour (all-in: power, cooling, depreciation)

- Planned runtime: 30 days

Cost

8,192 × 24 × 30 × $2

≈ $11.8 millionWith a 3× Silent Slowdown

- Runtime becomes 90 days

- Same GPUs

- Same power draw

- Same staff

- Same opportunity cost

New Cost

≈ $35.4 millionHidden Costs (Bigger Than You Think)

Opportunity Cost

- Model delayed 60 days

- Competitor ships first

- Lost market window

Resource Contention

- GPUs unavailable for next run

- Schedulers jammed

- Cascading delays across org

False Confidence

- No failures logged

- No restarts

- Leadership assumes plan is intact

This is why hyperscalers treat tail latency regressions as financial incidents.

Final Unified Truth

All four pieces connect:

- RoCE fabrics survive microbursts only if buffers buy time

- Gray failures are invisible unless GPU + network telemetry is fused

- Training fabrics are synchronization engines, not networks

- A 3× slowdown silently burns tens of millions of dollars

The core reality:

AI infrastructure does not fail loudly. It fails by wasting time.

And in AI, wasted time is the most expensive failure of all.

Below is a field-grade, crisis-driven explanation of all three topics—why teams revert to InfiniBand mid-incident, what real gray-failure post-mortems look like, and how on-prem vs cloud AI fabric economics actually compare when things go wrong.

This is written the way it’s discussed after millions have already been burned.

1) Why Orgs Revert to InfiniBand Mid-Crisis

The Situation

- Large LLM training job running

- RoCE fabric “healthy”

- No packet loss

- No link flaps

- Step time slowly creeping up

- GPUs increasingly idle between kernels

Leadership asks the worst question:

“Can we make it finish faster now?”

Why InfiniBand Becomes the Escape Hatch

1. Determinism Beats Optimization

InfiniBand’s credit-based flow control means:

- No PFC storms

- No pause propagation

- No microburst tuning

- No ECMP roulette

It trades peak flexibility for guaranteed behavior.

In a crisis, predictability > elegance.

2. Debug Time Collapses

With RoCE, to diagnose gray failures you must inspect:

- ECN thresholds

- PFC hysteresis

- Queue carving

- ECMP entropy

- Optics FEC margins

- GPU idle telemetry

With InfiniBand:

- If credits exist, packets flow

- If they don’t, they don’t

- Congestion is explicit and local

Mean time to understanding drops from weeks to hours.

3. Human Factors Matter

At 3 a.m.:

- Few engineers deeply understand RoCE tuning

- Many HPC engineers understand InfiniBand

When money is burning per hour, organizations choose known physics over clever abstraction.

The Pattern You See Repeatedly

- RoCE deployed for scale and cost

- Gray failure appears mid-training

- Job falls behind schedule

- “Just make it finish” mandate

- Temporary or permanent InfiniBand reversion

InfiniBand is not winning on ideology.

It’s winning on operational certainty.

2) Real Gray-Failure Post-Mortems (What They Actually Say)

Below are composite but realistic post-mortem patterns pulled from multiple large AI orgs.

Post-Mortem A: “The Invisible Optic”

Symptom

- Training run 2.6× slower than projected

- No alerts

- No packet loss

- GPUs show ~18% idle per step

Root Cause

- One 400G optic with marginal OSNR

- FEC correcting bursts during AllReduce

- Adds ~4–6 µs jitter on one path

Why It Hurt

- That GPU group became the straggler

- Entire collective waited every step

Lesson Learned

“Links that are ‘up’ are not necessarily usable for synchronous compute.”

Post-Mortem B: “The Helpful Hash Change”

Symptom

- Gradual slowdown over 48 hours

- No configuration alarms

- ECMP utilization looked balanced (on average)

Root Cause

- Firmware update changed ECMP seed

- Hash collisions aligned collective flows

- One spine path became consistently overloaded

Why It Hurt

- Deterministic imbalance

- Same GPUs late every step

Lesson Learned

“Randomization changes are not neutral in synchronized systems.”

Post-Mortem C: “The Metrics Lied”

Symptom

- Job progressing

- Loss decreasing normally

- ETA quietly drifting out by weeks

Root Cause

- PFC pauses occurring for microseconds

- Never long enough to trigger alerts

- Happening every training step

Why It Hurt

- Checkpoints masked delay

- Schedulers saw “healthy” progress

Lesson Learned

“A system that preserves correctness can still destroy economics.”

3) On-Prem vs Cloud AI Fabric Economics (The Uncomfortable Math)

This comparison only makes sense once gray failures are included.

A. On-Prem AI Fabric Economics

Costs

- Capital intensive upfront

- Fiber, switches, optics owned

- Staff expertise required

Benefits

- Full control of physical layer

- Deterministic latency

- Ability to retire marginal optics immediately

- Stable performance over long runs

Risk Profile

- Failures are visible

- Fixes are local

- Slowdowns are usually explainable

On-prem fails loudly.

B. Cloud AI Fabric Economics

Costs

- No capex

- Pay per GPU-hour

- Fabric is opaque

Benefits

- Elastic scale

- Fast startup

- No physical maintenance

Risk Profile

- Gray failures invisible to customer

- Performance variability tolerated contractually

- Tail latency not guaranteed

Cloud fails quietly.

The Brutal Cost Reality

Assume:

- 8,000 GPUs

- $2–$4 per GPU-hour effective cost

- Planned 30-day run

| Scenario | Runtime | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect fabric | 30 days | ~$12–$24M |

| 2× slowdown | 60 days | ~$24–$48M |

| 3× slowdown | 90 days | ~$36–$72M |

Cloud bills every hour regardless of efficiency.

On-prem amortizes inefficiency over owned assets.

Why Some Orgs Replicate On-Prem in the Cloud

They try to:

- Pin instances

- Isolate clusters

- Use dedicated fabrics

- Avoid noisy neighbors

Which quietly turns:

“Cloud flexibility”

into

“On-prem costs without on-prem control”

Final Synthesis (All Three Together)

- Orgs revert to InfiniBand when time certainty matters more than elegance

- Gray failures don’t crash jobs — they bleed time

- Cloud hides fabric problems behind abstraction

- On-prem exposes them but lets you fix them

The core operational truth:

AI infrastructure rarely breaks. It merely stops being worth the money.

And when that happens mid-run, teams don’t debate ideology.

They choose whatever finishes fastest and predictably, even if it looks “old-school.”